This is the final blog in the series exploring high-leverage instructional strategies to strengthen Tier 1 instruction. The first blog focused on setting the stage for success before instruction. The second blog explored strategies for delivering engaging, accessible, and effective instruction. This final blog examines how teachers can use what they learn during Tier 1 instruction to make informed decisions about the next steps—identifying students who may need Tier 2 support and those ready for enrichment or extension.

Related Podcast Episode

Assessing student learning is a lot like refining a recipe.

Great chefs don’t just serve a meal and move on. They pay close attention to how diners respond to the meal. They watch for reactions, listen to feedback, and make adjustments to improve future dishes. Did everyone enjoy the meal? Did some dishes return to the kitchen only partially eaten? Did some dishes need additional seasoning, or would they benefit from being paired with a different side? This reflective process ensures that every dining experience improves over time.

Similarly, effective Tier 1 instruction isn’t just about delivering content. It’s about assessing student learning in real time and using that information to determine what comes next. Each lesson provides valuable insights into who needs more support, who is ready for a next-level challenge, and what adjustments need to be made moving forward.

In this final blog in the series on Tier 1, I want to explore the following questions:

- How do we collect and use informal data to make informed decisions about what should follow Tier 1 instruction?

- How do we determine which students need Tier 2 support or enrichment?

It’s critical that teachers, like chefs, adjust their instruction and support based on what they learn from their students about the effectiveness of instruction. By closing the loop on Tier 1 instruction, we can ensure that all students make progress, whether they need additional support or opportunities to extend their learning.

Using Tier 1 Instruction to Gather Meaningful Data

Tier 1 instruction isn’t just about delivering content. It is an opportunity to collect real-time data on student learning. As students engage with new concepts—as they watch videos, engage with each other during a whole-group lecture, or receive differentiated small-group instruction—their progress, participation, and performance offer valuable insights into what they know, understand, and can do. This informal data allows teachers to identify who is on track, who needs additional instruction or support, and who is ready for enrichment.

The best way to ensure instruction remains responsive is to include strategies for collecting formative assessment data in each lesson. This allows teachers to make informed instructional decisions about what additional differentiated or personalized instruction, support, and feedback may be necessary. Formative assessment data positions students to be responsive to student needs in each lesson instead of relying solely on summative assessments at the end of a unit to understand what students know or can do.

What Data Sources Can Help Teachers Determine Next Steps?

Teachers can use multiple data sources to assess student learning and decide whether to reinforce, reteach, or extend instruction:

- Formative Assessments: Exit tickets, quick writes, student reflections, and checks for understanding offer immediate insights into what students understand and struggle with.

- Observational Data: Student participation in discussions, collaboration in group work, and independent work habits provide key indicators of comprehension and engagement.

- Student Self-Assessments: Encouraging students to set goals and reflect on understanding helps them develop their metacognitive skills and provides teachers a window into their perceived levels of competence and confidence in relation to specific concepts and skills.

- Digital Tools & Platforms: Adaptive learning software, quizzes, and practice tasks provide real-time performance data, helping teachers to identify trends in students’ learning.

Embedding formative assessment data into daily instruction makes it possible to close the loop on Tier 1 instruction, ensuring that all students get the support or challenge they need to continue progressing toward standards-aligned learning goals.

Identifying Students Who Need Tier 2 Support

Tier 1 instruction provides the foundation for all students, but some students will need more targeted support to reach mastery of specific concepts and skills. Tier 2 intervention is designed for students who struggle to meet grade-level standards despite having access to high-quality Tier 1 instruction. Students who need Tier 2 support may simply need more time, a different instructional approach, guided practice, or additional scaffolds to develop the skills and understanding necessary to move forward successfully in the curriculum.

Key Indicators That a Student May Need Tier 2 Support

Not every student who struggles during a lesson requires Tier 2 intervention. Some may benefit from additional Tier 1 reinforcement, while others need more intensive, small-group support to close learning gaps. Teachers can identify students in need of Tier 2 intervention by looking for:

- Persistent misconceptions or misunderstandings.

- Difficulty finishing tasks independently.

- Noticeably slow progress in relation to their peers, even with scaffolding and differentiation.

- Persistent mistakes or errors that are not improving.

- Incomplete or incorrect work.

- Visible frustration or stress when working.

- Low scores or incorrect answers on formative assessments.

Once we identify students who are not making the necessary progress, the next step is determining what support will help them move forward.

What Does Tier 2 Support Look Like In Action?

Tier 2 intervention does not repeat Tier 1 instruction in small groups. It should not feel like more of the same instruction. That approach did not help the students understand a concept or skill, so Tier 2 needs to be more personalized, scaffolded, and responsive to specific student needs. Effective Tier 2 may include the following strategies:

Small Group Reteaching

Small group reteaching allows the teacher to provide targeted instruction focused on specific skills or concepts students struggled with in Tier 1. This instruction should be intentional and data-informed, not just reviewing the material in the same way as it was presented for the whole class.

For example, if a formative assessment shows that several students misunderstood how to identify the main idea in an informational text, reteaching should go beyond restating the original explanation. Instead, the teacher can take a different approach by using one or more of the following strategies:

- Use a different instructional approach, such as highlighting key details and modeling how to summarize supporting evidence.

- Model the process with a think-aloud, making your thought process explicit for students so they can hear what you are thinking as you work to identify the main idea in a text. After modeling the process, guide students in replicating the strategy as they attempt to identify the main idea in a new text.

- Provide sentence stems to scaffold student thinking. Have students work in pairs to verbalize their reasoning before applying the skill independently.

- Work backward and provide students with a concept map that has the main idea identified in the center. Then work with the student to find details in the text that support that main idea, encouraging the student to surface their thinking.

By shifting the instructional approach, small group reteaching gives students a new way to engage with the concept or skill rather than simply hearing the same explanation again.

Scaffolds

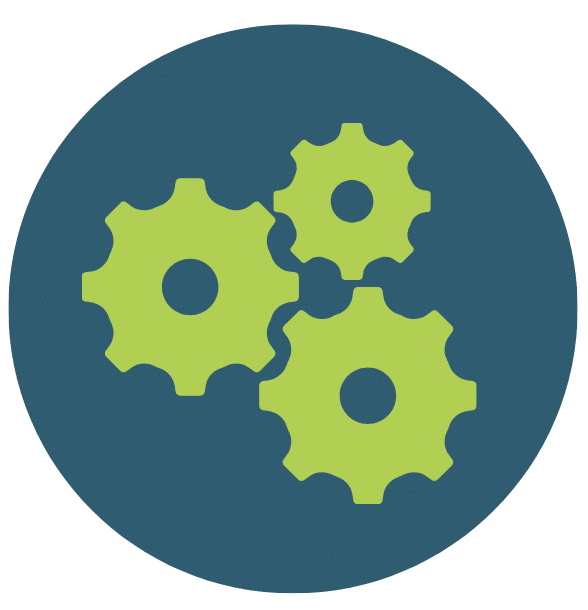

Scaffolds provide support to help students access the content in different ways. They may include comprehension aids, like graphic organizers, sentence stems, deconstructed examples, and anchor charts, which make complex tasks more manageable and learning more accessible.

For example, if students struggle to write a strong argumentative paragraph, an argumentative writing organizer can help them structure their ideas more effectively. It provides essential support by explaining the purpose of each part of the paragraph and offering sentence stems to help students articulate their thinking.

Chunking

Chunking involves breaking down complex concepts into smaller, more manageable steps and gradually releasing responsibility to students. This helps prevent cognitive overload and makes learning more accessible.

For example, if students struggle with a multi-step word problem in math, chunking can help them process information in smaller, digestible parts before solving the entire problem. Instead of presenting the problem at once, the teacher can:

- Identify and isolate the key information. Reveal only the first step of the problem and prompt students to identify what information is provided and what is missing before proceeding.

- Model one step at a time. Solve the first operation together, discussing the reasoning behind it before progressing to the next step.

- Provide guided practice. Have students replicate the process with a partner, verbalizing their thinking as the teacher listens and observes.

- Encourage independent practice. Once students demonstrate an understanding of each step in isolation, have them apply the full process independently.

By chunking the problem-solving process, students develop confidence, avoid cognitive overload, and develop a clearer understanding of how to work through complex problems step by step.

Alternative Instructional Approaches

Shifting strategies when providing Tier 2 support is critical to better meeting students’ learning needs. Teachers can use hands-on activities, discussion-based learning, working with examples and non-examples, or additional modeling to make concepts more accessible.

For example, if students struggle to grasp the concept of phase changes in a science unit on states of matter and phase changes (e.g., melting, freezing, evaporation), re-explaining the concept is unlikely to meet their instructional needs. Instead, the teacher can shift to a hands-on, inquiry-based approach.

They can provide hands-on experimentation using ice cubes, beakers of water, and a heat source. Students can observe and document physical changes in real time, recording temperature changes and describing what they see at each stage.

This tactile, exploratory approach gives students a concrete experience with phase changes, allowing them to observe the process rather than just hearing about it. By actively engaging in the experiment, students develop a deeper conceptual understanding and retain information more effectively.

Identifying Students Ready for Enrichment and Extension

While some students need additional support, others will demonstrate early and consistent understanding of concepts and mastery of skills. They are ready for more advanced challenges that go beyond the core curriculum. Enrichment and extension opportunities are designed to challenge students to show readiness to engage in higher-level thinking, explore topics more deeply, and apply their knowledge in new and creative ways.

Students who are ready for enrichment don’t just complete tasks quickly. They demonstrate a strong grasp of the content, ask thoughtful questions, and may seek out related information or make advanced connections between concepts. Instead of simply giving them more grade-level work to keep them busy, enrichment activities ensure these students remain engaged rather than feeling bored or unchallenged by learning activities that do not stretch their thinking.

Key Indicators That a Student May Be Ready for Enrichment

Not every student who finished early is ready for enrichment. The following signs may indicate that students are ready for advanced challenges.

- Demonstrates consistent mastery of lesson objectives across multiple learning activities.

- Asks questions that reveal a deeper level of understanding.

- Shows initiative to explore related topics or make connections beyond the lesson.

- Exhibits curiosity, creativity, or problem-solving.

- Applies the content or skill to new, novel, or real-world situations.

Once teachers have identified students ready for more challenging tasks, they can design enrichment that helps them stretch and grow in their conceptual knowledge and skill set.

What Does Enrichment and Extension Look Like in Action?

Enrichment and extensions should not mean “more work”—they should offer meaningful opportunities to think deeply, creatively, and critically. These learning activities should help students go beyond surface-level learning and apply their knowledge in new contexts.

Choice-Based Learning Extensions

Teachers can give students a menu of 2-4 options to extend their learning in a direction that interests them. These could include creative projects, inquiry-based research activities, design challenges, or cross-disciplinary tasks that allow students to explore how a concept connects to the real world.

For example, after mastering the concept of ecosystems, students could choose to create a video documentary about a specific biome, design a food web for a fictional environment of their creation, or research how human activities are impacting the local ecosystem.

Higher-Order Thinking Tasks

Higher-order thinking tasks provide students with opportunities to analyze, evaluate, or create based on what they have learned. This could involve complex problem-solving, spider-web discussions, reciprocal teaching with multimedia, or open-ended questions that require students to justify their reasoning.

For example, in an English class, instead of answering comprehension questions about a literary text, teachers can ask students to compare two authors’ perspectives on a similar theme or rewrite a scene from a different character’s point of view.

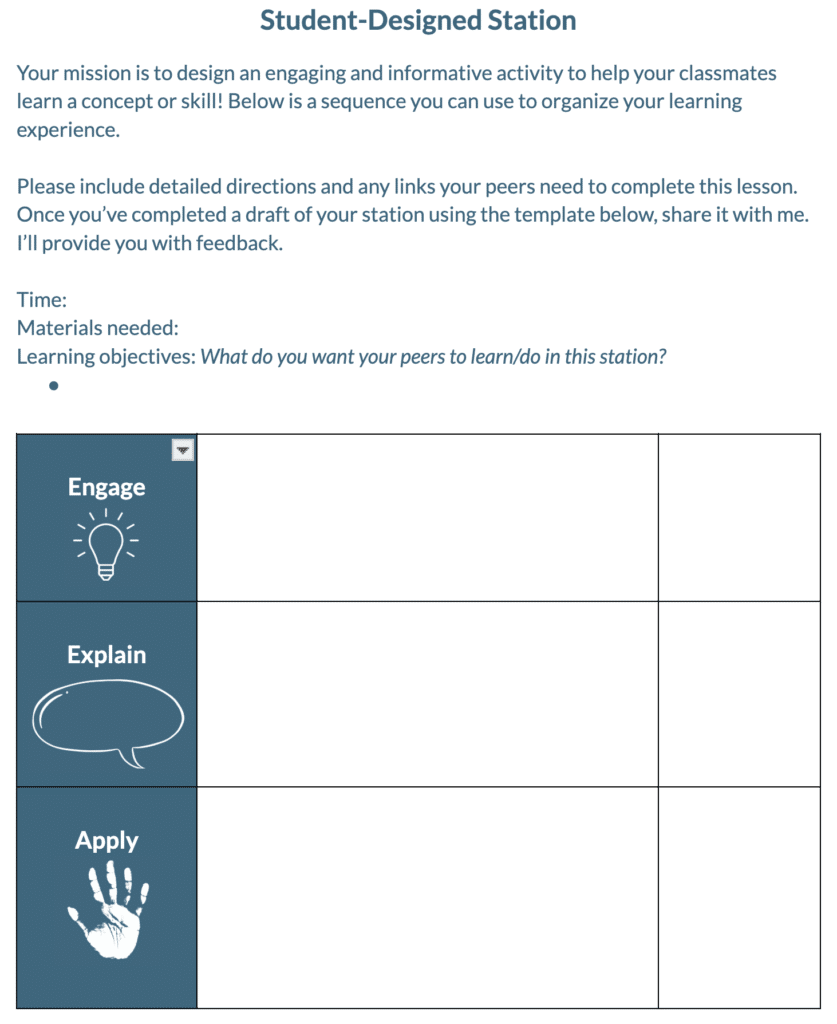

Student-Created Content

Student-created content is a wonderful way for students to teach one another, which is a powerful way for them to solidify their understanding of concepts, skills, and processes. Teachers can ask students to design learning experiences to help their peers learn.

For example, in a math unit, students who have mastered the content can create a video lesson, design a learning activity or station, construct a helpful model or analogy, or facilitate a review session for their peers.

Cross-Disciplinary Projects

Cross-disciplinary projects help students apply their knowledge and skills in authentic, interdisciplinary ways that mirror real-world tasks. These projects encourage students to draw connections between subjects and consider how knowledge is used outside the classroom.

For example, during a science unit on natural disasters, students could research how a specific disaster (e.g., earthquake, hurricane, wildfire) has impacted a particular region from a scientific and socioeconomic perspective. They might explore the geographical cause of the event, analyze data about its environmental impact, and investigate how local communities responded or rebuilt. Students could present their findings as an infographic, podcast episode, or policy proposal.

Wrap Up

Strong Tier 1 instruction doesn’t stop when the lesson ends—it continues as we reflect on what students learned and what they need next. Using the data gathered during Tier 1 instruction—through formative assessment, observation, student self-assessment, and performance data—we can make responsive decisions that support every learner’s growth.

Some students may need Tier 2 intervention, which may require more time, more targeted instruction, and different scaffolds to close learning gaps. Others may be ready for enrichment and extension, which involves opportunities to explore, apply, and deepen their learning in new ways. The goal is not to label students but to use what we learn during instruction to ensure all students move forward. For more instructional strategies teachers can use to create time in class for Tier 2 support or extension, check out my blog, “MTSS: Instructional Strategies to Make Time for Tier 2 Support and Extension.“

This three-part blog series was designed to help teachers think intentionally about before, during, and after instruction—recognizing that each phase is critical in creating a classroom where learning is inclusive, dynamic, and responsive. When we build strong Tier 1 systems that support, stretch, and challenge students at all levels, we create the conditions for every learner to thrive.

No responses yet