Many of the schools I work with have adopted curricula in response to updated state standards and growing pressure to improve student outcomes and close achievement gaps. The decision to adopt and pay for a curriculum is driven by a range of considerations. Curriculum design is time-consuming, cognitively demanding work. Providing teachers with a high-quality, already developed curriculum frees them to focus on facilitating learning, providing feedback, and building relationships. Leaders also want consistency across classrooms, so that all students, regardless of the teacher or school site, have equitable access to rigorous, standards-aligned learning experiences. District-level adoptions support this desire for consistency and help ensure alignment with required standards and assessments.

The adopted curriculum also provides a common foundation for teacher collaboration and work in professional learning communities (PLCs). Teachers working with the same set of resources can share strategies, analyze data, and learn from each other’s implementation of the adopted program. It also simplifies professional development, making it possible to provide targeted learning opportunities focused on the specific curriculum teachers are using. The vetting process used when adopting curriculum is also designed to ensure that teachers are provided materials grounded in research and best practices.

These are all valid and worthwhile reasons to adopt a curriculum. However, curriculum adoptions can also create tension on a campus. Teachers may fear that programs will reduce the importance of their role as designers and facilitators of learning, especially if school leaders stress the expectation that teachers use the program with “fidelity,” implementing it exactly as it is written. This language leaves many teachers feeling like they are not allowed to adapt or modify the lessons to meet their specific students’ needs. That leaves little room for professional judgment, creativity, or responsiveness, which can feel stifling. And the reality is that if teachers are feeling frustrated and stifled, students feel it too.

Curriculum provides consistency, but it is teacher creativity and engagement that sparks interest, curiosity, and engagement in students. Schools cannot afford to lose either.

Mindset Shift: The Value of Adopted Curriculum

Despite the benefits an adopted curriculum provides in terms of alignment and consistency, it presents challenges as well. Many adopted programs are designed for a whole-group, teacher-led delivery, which makes it challenging to differentiate instruction and support. Teachers committed to meeting the diversity of needs in a class may find themselves frustrated when every lesson is written as if thirty students will progress in lockstep. While new or untrained teachers may find comfort in the structure, experienced educators can feel like their expertise, instincts, and knowledge of their specific group of students are being sidelined and undervalued.

This is why reframing how we approach adopted curriculum is essential. Curriculum should be seen as the foundation: it establishes clear learning goals, aligns with specific standards, and draws on research-backed best practices. The real work of teaching happens in the space between the foundation a curriculum provides and the lived experience of working with a unique group of learners. That is where teacher creativity belongs. It is what makes learning engaging, authentic, and responsive to the needs of a specific class.

When teachers are trusted to adapt an adopted curriculum to meet the needs of their learners, they experience increased autonomy and competence. These are two of the three psychological needs that drive human motivation. Autonomy refers to having choice and the ability to use professional judgment in how they teach, while competence is the belief in their capacity to effectively support all students making progress toward firm, standards-aligned learning objectives. As a result, educators stay more engaged and passionate about this work.

For students, autonomy is having meaningful choices in how they engage with their learning, while competence is the belief that they are capable of meeting academic challenges and making progress. When students experience both, they are more likely to be motivated, take academic risks, and feel more confident in themselves as learners. When schools create the conditions for both teachers and students to experience autonomy and competence, they cultivate a positive feedback loop: motivated teachers design more engaging learning, and engaged students fuel teacher satisfaction and retention.

The shifts described in this post create the conditions needed for autonomy and competence. When lessons are modified with these in mind, we can move beyond scripted compliance and create responsive and engaging classrooms where all students feel seen, supported, and successful.

Skill Set Shift: From Compliance to Creativity

Shifting from scripted compliance to creative engagement requires using the curriculum to ground instruction, while reclaiming the role of designer. Teachers must separate the “what” from the “how.” The curriculum defines what is taught and identifies the goals students are expected to reach, but teachers should use their knowledge of their students to thoughtfully modify and differentiate so that all learners make progress toward firm, standards-aligned learning goals.

From Whole Group to Small Group Engagement

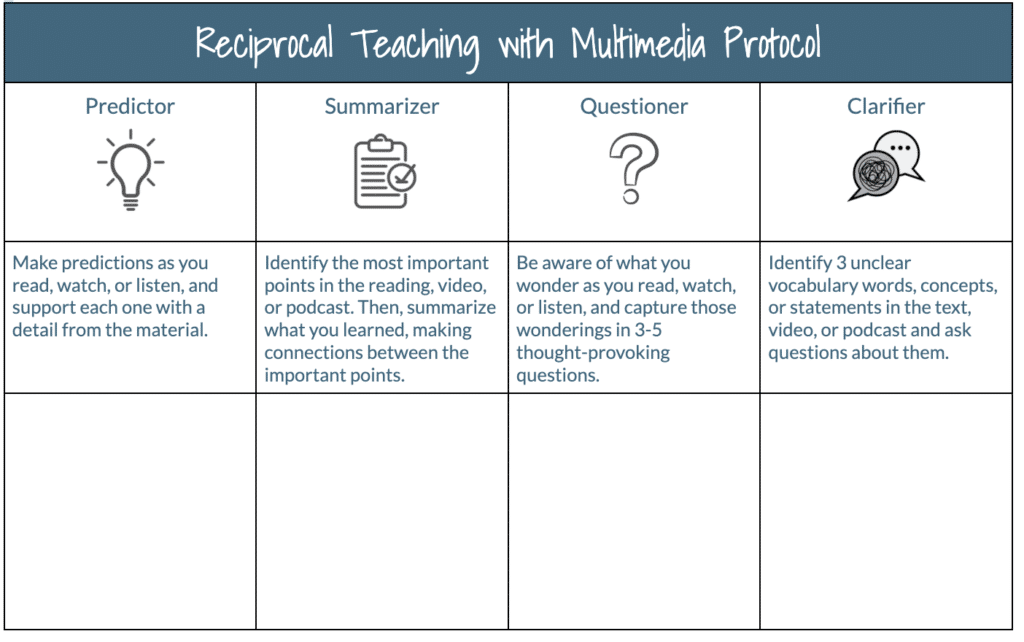

If a literacy program asks students to read and actively engage with a text, teachers may want to shift from a whole-class reading and discussion to using an inclusive reading comprehension strategy, like reciprocal teaching. Reciprocal teaching positions small groups of students to work collaboratively to read and make meaning together using specific comprehension lenses—predictor, summarizer, questioner, clarifier.

This small group dynamic may make it less intimidating for students to unpack and discuss a complex text. It also requires that the students, not the teacher, do more of the cognitive work since they must work together to unpack the text. This small shift also frees the teacher to facilitate a scaffolded small-group reading with students who might need additional support in understanding the text.

From One Pathway to Flexible Pathways

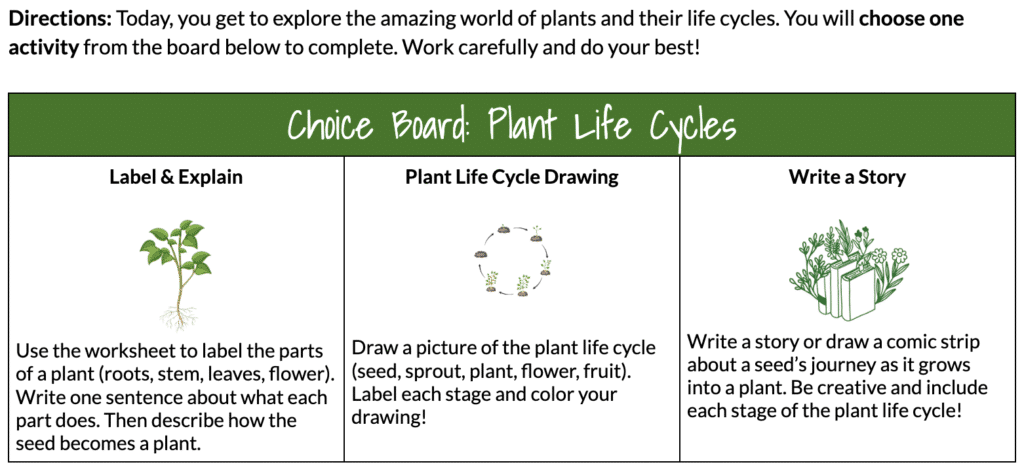

Teachers can also consider using choice boards to incorporate more student agency into the lessons in their curriculum. For example, if a science curriculum provides students with a worksheet asking them to label the parts of a plant and explain how a seed becomes a plant, the teacher can provide meaningful, construct-specific options with a simple choice board like the one pictured below. Choice boards strive to honor the variability in a classroom, appealing to different learner strengths and preferences.

Teachers who want to provide students with agency can identify a task or activity in the curriculum they think would benefit from more meaningful choices and use an AI chatbot to brainstorm construct-specific options for a choices board. This approach saves time and sparks new ideas while maintaining focus on the original learning goal.

From Basic Practice to Deeper Thinking

Many curriculum programs emphasize practice through online problem sets, worksheets, or repetitive drills. While these activities can reinforce skills, they are focused on students getting the correct answer. They may not drive deeper thinking about concepts, skills, or processes. In fact, only about 40-45% of teachers surveyed about their adopted curricula reported that it helped students “communicate complex concepts to others in both written and oral form,” “extend their core knowledge to novel tasks and situations,” or “routinely reflect on their learning experiences and apply insights to subsequent situations” (Seaman & Seaman, 2020). So, students might learn to “do the math,” but they often lack opportunities to explain their reasoning, reflect on errors, think creatively, or make connections to life beyond the classroom. That is where extension opportunities become powerful.

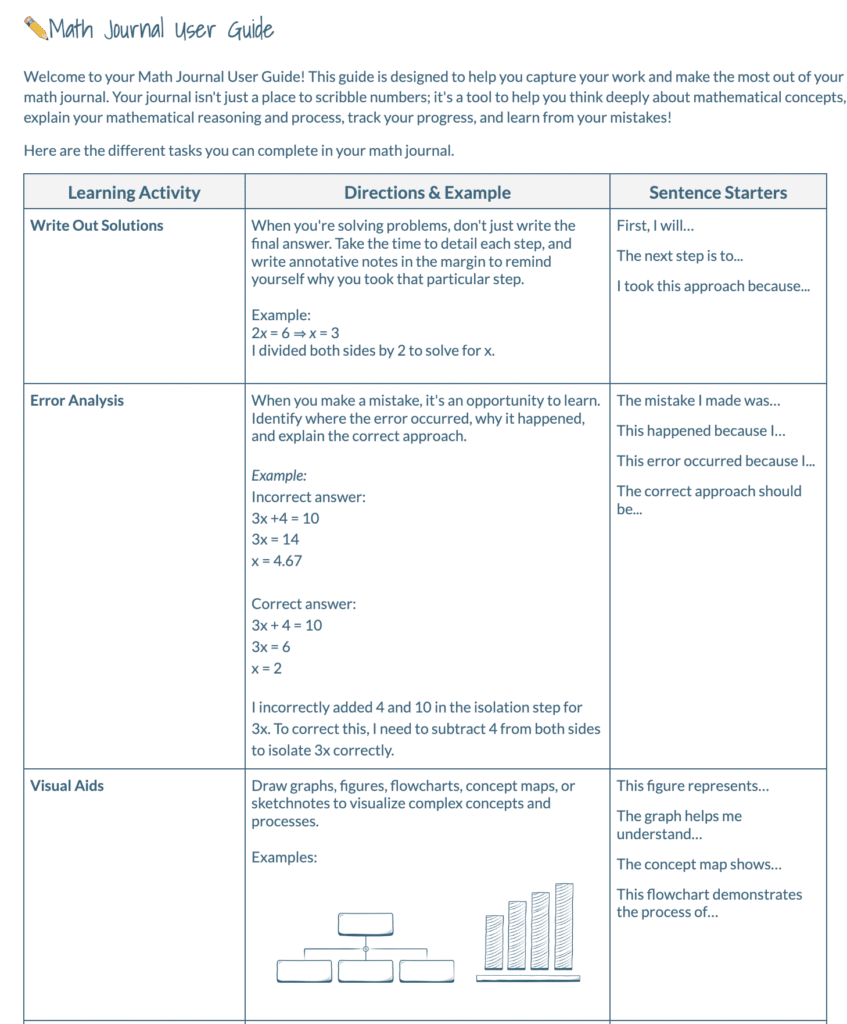

For example, teachers using a math curriculum might use a math journal to complement and extend their curriculum. A math journal encourages students to write in math, explain their mathematical reasoning, and creatively apply what they are learning. Instead of simply solving a list of problems, students can use their journals to show and explain their work, reflect on mistakes, and connect math to real-world problems. For example, after completing a set of equations, students might:

- Write out each step of their solution and explain why they chose that particular approach.

- Identify and analyze an error they made, describe why it happened, and explain how they corrected it.

- Create a flowchart, sketchnote, or concept map to visualize a strategy or process.

- Write a high/low reflection identifying a concept they understand and feel confident about, and one that is challenging and they need more support working with.

Using a math journal, like the one pictured below, can transform a set of practice problems into an opportunity for students to document their thinking and reasoning, identify patterns in their mistakes, surface areas of confusion, ask for help, and make meaningful connections between what they are learning and their lives beyond the classroom.

Creating a math journal to pair with the adopted curriculum honors student voice and preference because it provides multiple ways to engage with the content, from writing to drawing to reflecting. They also provide teachers with invaluable insight into their students’ thinking, not just whether they got the correct answer. As a result, routine practice transforms into an extension opportunity that can deepen our students’ understanding and develop their metacognitive muscles.

From Whole Group to Small Group Instruction

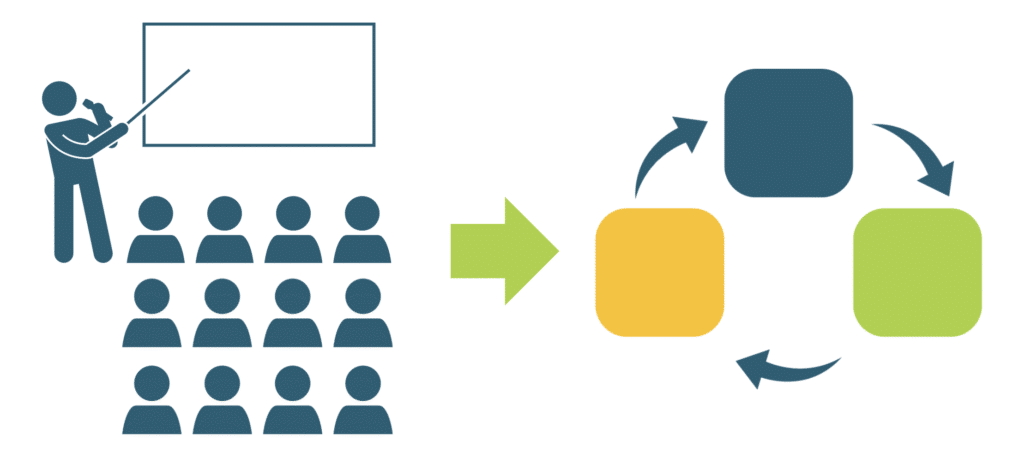

Many adopted curricula still rely heavily on whole-class, teacher-led instruction that follows a gradual release from “I do” to “we do” to “you do.” These lessons assume every student will move through the same instructional session, text, or activity at the same pace and at the same level of readiness. While that structure feels efficient, it often fails to address the wide range of skills, language proficiencies, and instructional needs in a classroom. Shifting from whole group to differentiated small group instruction allows teachers to honor the goals of the curriculum while adapting the delivery to better meet the needs of diverse groups of learners.

Not every lesson needs to be delivered in small groups. Whole group instruction is ideal for launching a new unit, building background knowledge, or sparking curiosity through a shared discussion where every student benefits from hearing the same ideas. But whole group instruction doesn’t always serve the wide range of needs in a classroom. Learning to identify what would be best presented in whole group versus differentiated small groups can help teachers adapt their curriculum to be more effective.

Questions to consider when debating whether to present concepts or skills in small groups:

- Does pre-assessment or formative assessment data reveal that students are in very different places and need different levels of support?

- Is the concept, skill, or process particularly challenging, nuanced, or complex, making it more effective to provide additional guidance in a smaller group setting where you can tailor the explanation and support?

- Would a small-group structure allow you to scaffold, reteach, or extend learning in ways a whole-class lesson cannot?

When the answer to one or more of these questions is “yes,” differentiated small group instruction can be the more effective choice. It creates more targeted support and higher levels of engagement while ensuring the whole class is making progress toward the same learning goal.

For example, imagine that an ELA lesson focuses on analyzing the author’s purpose in a text. Instead of trying to facilitate that analysis with 30+ students at once, the teacher can pull small groups and tailor the support using the station rotation model. At the teacher-led station, differentiation might look like this:

- For readers working below grade level or multilingual learners who may encounter language barriers, the teacher might preview or pre-teach key vocabulary, chunk the text into shorter passages, and read those sections aloud while modeling how to use context clues to uncover the author’s intent. In this small group setting, students practice with scaffolding and support, and they benefit from the immediate feedback and guidance the teacher provides.

- For readers working at grade level, the teacher can facilitate a collaborative close read of a passage, drawing attention to the language that reveals the author’s intent and prompting students to identify textual evidence that supports their interpretation of the text. In this small group session, students do more of the heavy cognitive lift while the teacher encourages deeper thinking with questions and timely feedback.

- For readers working above grade level, the teacher can increase the complexity of this small group session by asking students to compare the author’s purpose in this text to another piece or to evaluate how effectively the author’s purpose was achieved. In this setting, the students are challenged to think critically, make connections across texts, and support their conclusions with evidence.

In each of these teacher-led instructional sessions, the construct of analyzing the author’s purpose is the same. What changes are the teacher’s level of modeling and support, the complexity of the task, and the type of feedback provided. Differentiation at the teacher-led station ensures that every student is both supported and stretched in ways that a single whole-group instructional session could not accomplish.

The goal of these shifts is not to undermine the curriculum but to honor teachers’ creativity and their unique understanding of the students they serve. Fidelity should mean ensuring students achieve the intended learning goals, not implementing lessons without deviation. By moving from scripted compliance to creative engagement, schools can achieve a balance that benefits both teachers and students.

A Call to School Leaders and Instructional Coaches

For leaders and instructional coaches, messaging matters. When teachers hear “use the curriculum with fidelity,” they hear a directive to follow the lessons word for word. This leaves little room for professional judgment. It robs them of autonomy and may negatively impact their feelings of competence. And, by extension, it may cause some educators to feel frustrated, disillusioned, and unmotivated. Given the need to attract and retain high-quality educators, it is critical to clarify that the goal of using an adopted curriculum is to ensure all students master the learning goals identified in it, not rigid compliance with scripted lessons that may not meet students’ needs.

Equally important is recognizing that teachers need support not only in how to use an adopted curriculum, but also in how to adapt it with intentionality for diverse groups of learners. Too often, professional development stops at basic implementation—opening the box, learning the sequence, and following the lesson format. Research focused on curriculum adoption found that while 40% of educators rated the professional development they received in the top quarter of effectiveness, 60% rated it lower, with more than a third giving it a score under 50 (Seaman & Seaman, 2020). Not only are many teachers feeling that professional development is not adequately preparing them to use the programs being adopted, but they also need training that helps them to modify lessons in a way that maintains rigor, prioritizes student agency, and provides effective differentiation. This is where coaching and professional development can make the difference between compliance and engagement.

This is the work I am passionate about: helping schools and districts bridge that gap. Whether it is through virtual coaching sessions with instructional coaches or practice-based training with teachers using a particular curriculum, my focus is on supporting educators in adapting with purpose. The goal is to ensure the curriculum is meeting the needs of all students. If your team is navigating this challenge, I’d love to connect and explore coaching or training options that would be the best fit for your context!

No responses yet