Related Podcast Episode

In my last post titled Differentiation Made Doable: The Teacher-led Station in the Station Rotation Model, I shared how small-group instruction can make tailoring a lesson to students’ needs feel more realistic for teachers. That post focused on one instructional model. This post takes a step back to explore differentiation more broadly. Why does differentiation matter? What exactly does it mean? What does it look like in practice?

Why Differentiate?

At its foundational level, differentiation is simply good teaching.

Decades of practice and research suggest that tailoring instruction to students’ skill levels, learning preferences, and language proficiencies leads to better outcomes. When teachers use different strategies, adjust the complexity, and provide multiple examples, students gain more entry points to access the content. Differentiation increases our effectiveness in meeting the needs of all learners.

The benefits of differentiation are well-documented. Students in classrooms where teachers differentiate instruction and support demonstrate stronger achievement, have more positive attitudes toward school, and develop greater confidence in their abilities compared to students in one-size-fits-all settings. Matching instruction and tasks to a student’s current level of knowledge, skill, or readiness increases persistence and reduces both boredom and frustration. It makes sense that if learning is presented within the student’s zone of proximal development (ZPD), the range between what they can do independently and what they can do with guidance, they are more likely to be engaged in the learning and feel successful.

The ability to match instruction and support to students’ needs is critical in today’s increasingly diverse classrooms. As the gap between the highest- and lowest-performing students has widened, differentiation has shifted from a helpful teaching strategy to an imperative. In mixed-ability-level classes with a wide spectrum of skills, abilities, and language proficiencies, one lesson will not fit all–or even most. Without proactive differentiation, teachers often find themselves scrambling to provide scaffolds on the fly, relying on extended direct instruction sessions that only a portion of the class needs, and defaulting to activities or tasks that are either too hard for some or not challenging enough for others.

When the goal is bridging that growing gap while still supporting students on either end of the performance spectrum, what do we do? We tailor instruction to meet students’ individual needs, which is exactly how differentiation expert Carol Ann Tomlinson defines the term. She expands on that definition in an ASCD publication:

“Differentiating instruction means that the teacher anticipates the differences in the students’ readiness, interests, and learning profiles, and, as a result, creates different learning paths so that students have the opportunity to learn as much as they can as deeply as they can, without undue anxiety because the assignments are too taxing–or boredom because they are not challenging enough.”

Sounds great, right? But here’s the pushback I hear most often: “Perfect… Now I need 30 different lesson plans?”

The good news: differentiation doesn’t require that at all. Instead, it provides practical tools to address a wide range of classroom needs.

What Is Differentiation?

Differentiation doesn’t mean handing out 30 different worksheets. It’s about making smart adjustments across four areas—content, process, product, and learning environment—that help more students succeed.

Here are some easy-to-implement ideas you can reuse across multiple lessons. Think of them as starting points, not a checklist. The Station Rotation Model is also a great entry point to differentiating parts of your lessons, so I’ve included some station-specific ideas for you to try.

Content

- What it is: The information students are learning and how they access it.

- Why it matters: If students cannot access the material, they will not be able to make progress toward the standards.

- How to differentiate: Offer information in different formats (e.g., read, watch, listen, explore visuals) and provide texts and tasks at varying levels of rigor and complexity.

- Station rotation idea: Use the teacher-led station to provide tailored instruction for small groups while the online and offline stations provide additional opportunities for students to engage with concepts and skills.

Process

- What it is: The activities students engage in to understand new information or make meaning.

- Why it matters: Students process information in different ways. Some thrive in groups while others prefer to work alone. Some think best internally, while others need to talk ideas out. This variation means that a single strategy for supporting processing and meaning making is unlikely to work for all learners.

- How to differentiate: Offer different graphic organizers, use modeling and thinking routines, or provide “would you rather” options for meaning making.

- Station rotation idea: Design one station dedicated to meaning-making, but allow students to decide how they want to engage with the task (e.g., create a written analogy or engage in a small group discussion).

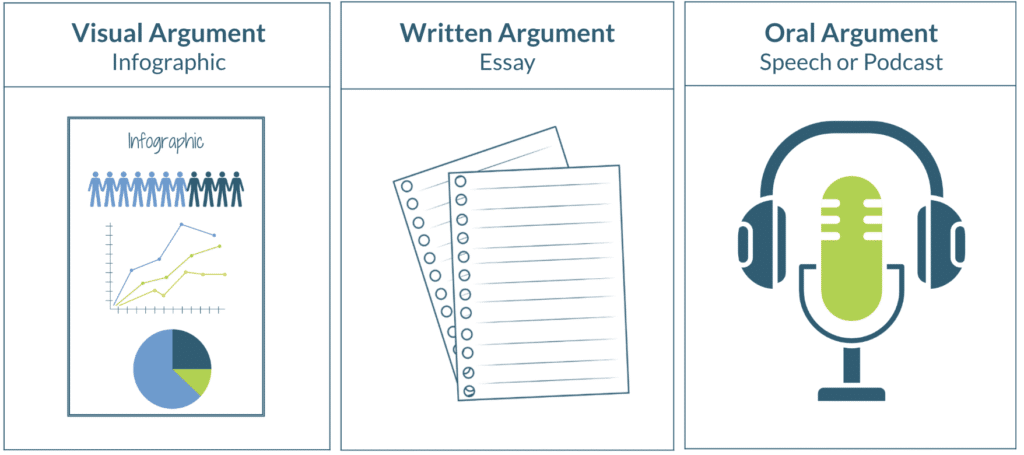

Product

- What it is: The assignments and projects that ask students to show what they have learned.

- Why it matters: Choice in products allows students to demonstrate understanding in ways that fit their preferences and strengths, providing teachers with a more accurate insight into and evidence of their learning.

- How to differentiate: Provide a choice board of options (e.g., essay, video presentation, artistic representation) and use asset-based rubrics to clearly communicate what success looks like at different levels of proficiency.

- Station rotation idea: Use the teacher-led station to provide feedback on products in progress, adjusting the level of support and scaffolding to each student’s specific needs.

Learning Environment

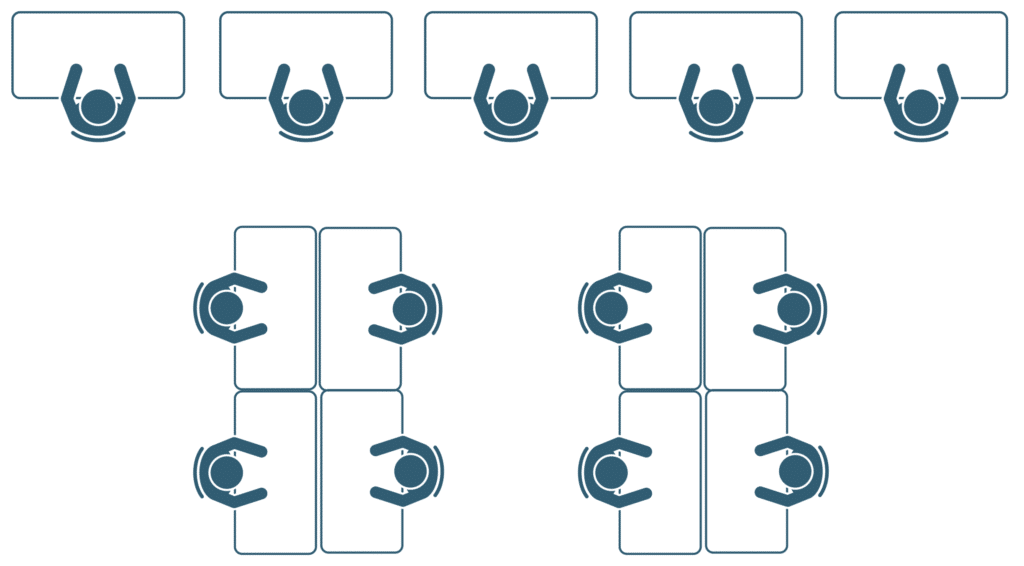

- What it is: The physical and/or online space where learning is happening.

- Why it matters: A flexible learning environment helps students focus and work productively.

- How to differentiate: Offer varied seating arrangements (e.g., rows along the wall for individual work and grouped tables for collaboration), learning zones for quiet and conversational activities, and options for more tactile offline tasks versus online digital work.

- Station rotation idea: Balance quiet, independent work with collaborative, conversational assignments and include a mix of online and offline stations.

Don’t feel like you have to differentiate all four areas at once. Start with one, build a routine that works, and expand from there.

What Does This Look Like in Action?

Here are three snapshots of classrooms that illustrate how differentiation can be implemented in manageable and reusable ways.

Differentiating the Content in Elementary

In a third-grade social studies unit on communities, the teacher prepares three versions of the same core material: a short article with visuals, an original podcast using NotebookLM, and an interactive online map. Teachers create these multimodal resources but are able to reuse them throughout the unit to ensure students have multiple entry points into the content.

During class, students rotate through the resources in small groups, which provides varied access, fosters collaboration, and creates opportunities for independent exploration. This flexible design honors learner variability while reducing the need for reteaching. It also allows students to practice self-direction as they engage with the content in ways that align with their strengths and needs. By differentiating content by providing information in multiple formats, the teacher ensures that every student has an entry point into the unit’s core ideas.

Differentiating the Process & Learning Environment in Middle School

In a seventh-grade math lesson on ratios, the teacher designs two practice stations: one with multi-step word problems for pairs to tackle collaboratively and another with scaffolded visuals and guided practice for students who need more structured support. Students are assigned a station (or can self-select) based on their readiness, ensuring that each learner engages with practice that matches their needs.

While students work, the teacher can use this time to provide targeted support either by circulating to monitor progress and answer questions or by offering Tier 2 support for students who are struggling and need more guided practice. Because stations are part of the classroom routine, the teacher doesn’t need to redesign the entire lesson daily; only the problem sets change.

The learning environment itself is also differentiated, with a row of desks facing the back wall for individual practice and table groups for the stations that require collaboration. This structure balances challenges with support, giving students opportunities to reflect on how they learn best and choose the space and task that best fit their needs.

Differentiating the Product in High School

In a tenth-grade English class, the teacher designs a choice board for the end-of-novel project. Students must present a clear argument about how a central theme is developed in a novel. The teacher provides three project pathways: an essay, a podcast episode, or an infographic. Each option targets the same standards and skills, so a single rubric applies across all products, ensuring fair and manageable grading. To scaffold the process, the teacher curates a bank of resources (articles, video clips, and character maps) and posts them to the class website or learning management system for anytime access.

During class, students decide whether to work independently, with a partner, or in a small group. While they work on their arguments, the teacher circulates to provide formative feedback on outlines or drafts, offering additional support to students who need it and posing probing questions to challenge those who are ready to delve deeper. This structure balances equity and efficiency: students exercise voice and choice in how they demonstrate learning, while the teacher develops a flexible assessment framework that can be adapted across future units.

Differentiation doesn’t require reinventing every lesson. It’s about building small, flexible structures into your planning that are easy to reuse and make fresh in future lessons. These structures reduce planning stress, increase student access to learning, and make differentiation sustainable over time. When integrated into Tier 1 instruction, they also shift classrooms toward prevention, supporting students before small struggles develop into larger gaps.

The Goal: Prevention Over Intervention

Differentiation is most powerful when it’s proactive, using strategies now that reduce the need for intervention later. By intentionally identifying and responding to students’ needs during Tier 1 instruction, we provide them with the right level of support before small struggles escalate into larger challenges. When teachers adjust the content, process, product, or environment up front, more students can access learning at the first level of instruction. This reduces the number of learners who require extra help in Tier 2 support and Tier 3 intervention. In other words, effective differentiation at the start prevents the cycle of catch-up later.

Currently, many classrooms are in the catch-up phase, relying heavily on interventions to bridge learning gaps. But with consistent, thoughtful differentiation, we can shift toward prevention, supporting students before those gaps widen. This shift benefits both students and teachers. Students access learning the first time it is taught, and teachers save time and energy by reusing flexible structures instead of scrambling to reteach. Differentiation is not about adding more to your plate; it’s about designing with intention so learning feels possible for every student, every day.

No responses yet