Every student deserves access to high-quality, grade-level instruction and learning experiences, regardless of the teacher. Yet many classrooms are led by educators who are early in their careers, teaching outside their areas of expertise, or stepping into teaching positions without sufficient preparation. At the same time, schools are grappling with persistent teacher shortages that make it increasingly difficult to ensure that every classroom is led by a fully qualified teacher. The Learning Policy Institute reports that one in eight teaching positions is vacant or filled by underqualified educators.

In response, many districts have turned to high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) to strengthen Tier 1 instruction at scale. HQIM provide structure, coherence, and instructional guidance that can help educators, especially those new to the profession or without formal teacher training, deliver grade-level content and rigorous learning experiences. HQIM stabilizes Tier 1 instruction by ensuring consistency across classrooms and reducing cognitive load for teachers, especially for those still learning the craft, while also giving more experienced educators a strong foundation they can adapt and extend.

High-quality instructional materials can raise the floor of instruction. The challenge is ensuring that they don’t quietly become the ceiling.

A Mindset Shift: HQIM as a Foundation, Not a Script

HQIM are often implemented with an emphasis on fidelity. There is sound reasoning behind this. When a district invests in a curriculum, leaders want teachers to learn how to use it first. It is a bit like learning to cook a new dish. It requires that we closely follow a recipe to understand the ingredients and process. However, once we have made that dish half a dozen times, we do not need to adhere to the recipe. Given our culinary preferences or the group we are cooking for, we might make adjustments to improve the dish. Similarly, the emphasis on fidelity when a program is adopted encourages teachers to understand and use a new curriculum with confidence.

Like a detailed recipe, HQIM reduces the number of instructional decisions teachers must make, models strong lesson design, and helps to ensure that students have access to grade-level tasks and content. In this context, following the materials closely makes sense. The challenge arises when that same approach is applied to every teacher, in every classroom, regardless of experience or needs. For experienced teachers, HQIM should not function as a script to be followed from start to finish. They should function as a shared foundation, a reliable set of high-quality ingredients teachers can draw from as they design learning experiences that respond to their students.

When instruction provides a single pathway, even high-quality learning experiences can create barriers for students who need more modeling, guidance, processing time, or a different entry point into the learning. They may also limit the potential of our advanced students, who crave more rigorous and complex assignments and tasks.

When teachers and the instructional coaches who support them view HQIM as high-quality ingredients rather than a fixed sequence, they can use them more flexibly to meet the wide spectrum of needs in a classroom. That flexibility includes making intentional decisions about when to shift from whole group to small group or offer multiple pathways through the same standards-aligned content.

From Recipe to Ingredients: Using HQIM Flexibly

Most HQIM are written primarily as whole-group, teacher-led lessons. Students progress through the same sequence of learning experiences simultaneously and at the same pace, regardless of their specific needs, language proficiency, or learning preferences. This single pathway through the content is designed to ensure coherence and access to grade-level, standards-aligned work; however, one pathway will always create barriers for some learners. The limitation of these materials is not in the quality of the instructional task, but rather the lack of flexibility in how teachers are instructed to use them.

In my work with schools and districts, I spend significant time helping instructional coaches and teachers to reimagine how they use their HQIM to ensure they are responding to student data, differentiating effectively, and giving students agency and meaningful choice. Rather than asking whether a lesson should be whole group or small group, a more helpful question is which parts of the lesson benefit from each structure.

Works Best in Whole Group

Using a provocation, hook, or activity to launch a new concept or unit of study

Building shared language/vocabulary or background knowledge

Surfacing questions and making predictions about the learning

Using a cooperative learning strategy, like Numbered Heads Together (NHT), during an instructional session

Articulating the why, or purpose and value, of the work and setting success criteria; establishing norms and expectations

Modeling a process that all students need to see

Works Best in Small Groups

Differentiated instruction and support for students at different levels of readiness

Differentiated modeling sessions to onboard students to a new strategy or skill that is complex

Addressing specific instructional needs identified through formative data

Guided practice with teacher support

Real-time formative feedback on work in progress

Teacher-facilitated discussions at different depths of knowledge

Providing Tier 2 support by scaffolding or extending learning

Questions to Guide Strategic Use of HQIM

Teachers and instructional coaches can begin shifting toward flexible implementation by asking strategic planning questions.

- Which parts of this lesson truly benefit from whole-group instruction and shared engagement? Which would be more effective in small groups?

- Who is most likely to struggle or disengage with this lesson as written? What instructional adjustments would remove those barriers?

- What data do I have access to that can help me use different parts of this lesson strategically to meet my students’ diverse needs?

- What evidence will tell me whether this instructional approach is working?

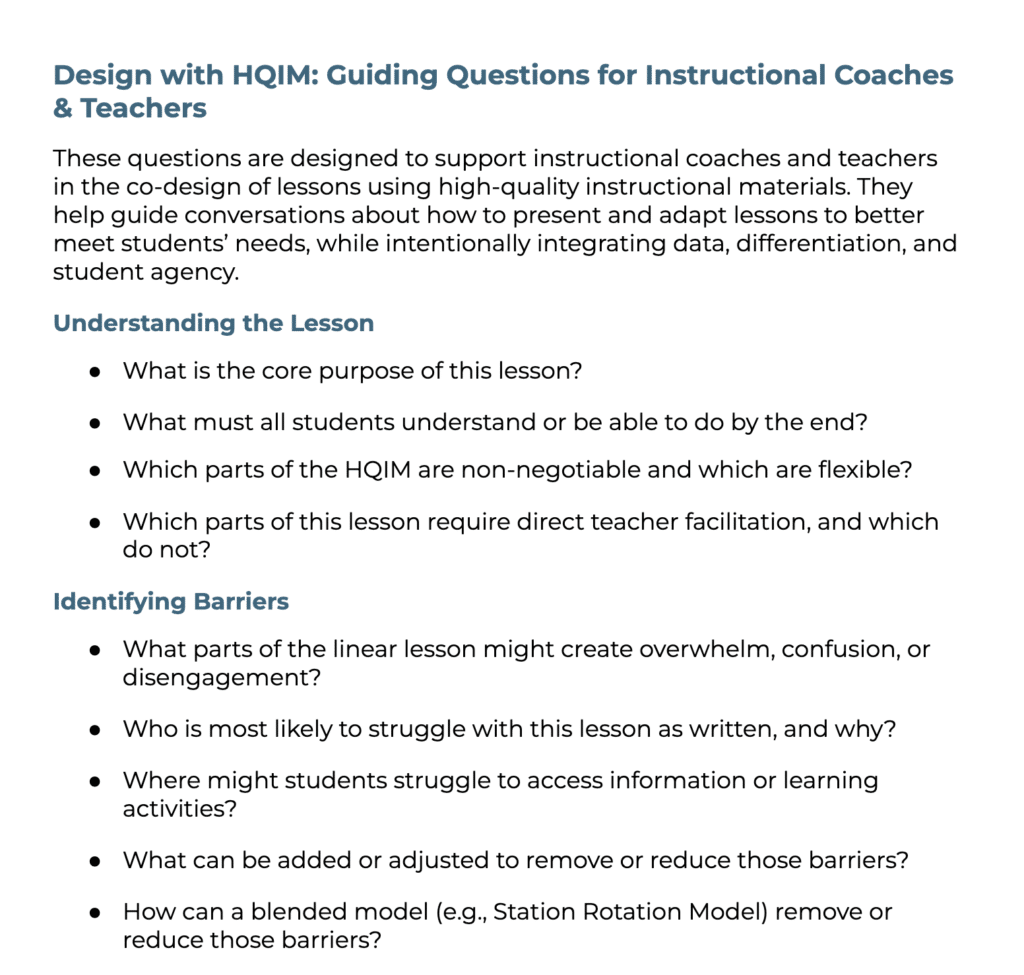

For teams that need a more complete question set to guide their use of HQIM, I developed the resource below. It is a more comprehensive set of guiding questions organized around understanding the lesson, identifying barriers, using data, differentiating, and giving students agency.

These questions give teachers and coaches a shared language for making instructional decisions. The following Bluebonnet example illustrates how that thinking can translate into a flexible lesson structure while preserving the integrity of the HQIM.

Bluebonnet Lesson: Reimagining HQIM for Access

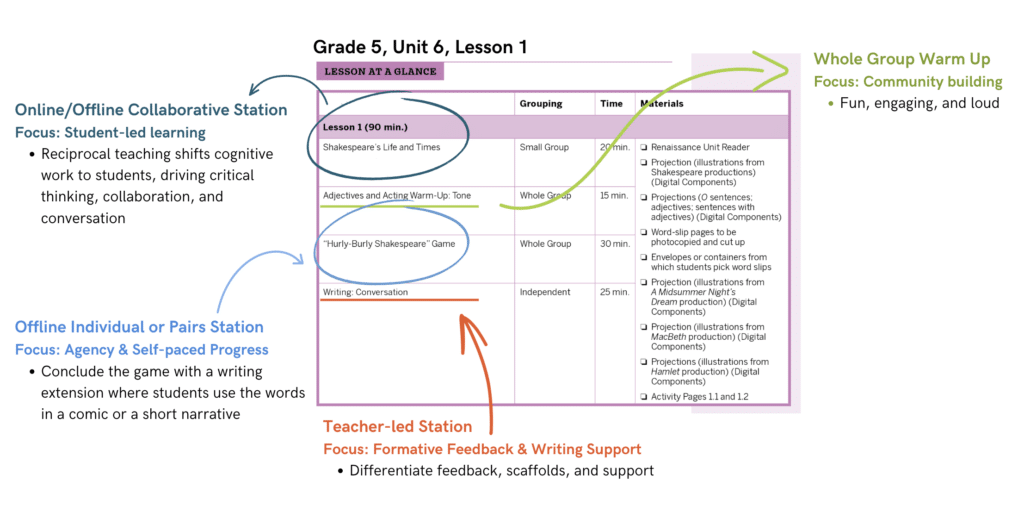

When I work with instructional coaches and teachers, it is essential to provide concrete examples of this reimagining. Below is an elementary ELA lesson from Bluebonnet Learning, the adopted curriculum in much of Texas, that I reorganized into a station rotation lesson.

The original lesson was designed as a whole-group experience. It opens with a lively language activity, moves into shared reading and discussion, and concludes with a writing task. All students engage with the same materials and prompts at the same pace.

The Reimagined Lesson at a Glance

| Instructional Structure | Learning Activity | Why This Works |

| Whole Group | Playful language warm-up and lesson launch | Builds community, shared context, and confidence before students transition into the lesson |

| Teacher-led Station | Writing task with differentiated modeling, feedback, and language support | Allows for targeted instruction, especially for multilingual learners and developing writers |

| Collaborative Station | Reciprocal teaching with HQIM texts | Provides an inclusive structure for students to process information at their own pace and make meaning with peer support |

| Independent or Partner Station | Language practice and application | Gives students control over the pace of their progress, reduces pressure to use language in front of the entire class, and provides repeated practice for multilingual learners |

Why I Kept The Whole-Group Opening

I intentionally kept the opening activity as a whole-group experience. It is energetic, playful, and a little loud. Students use their voices, experiment with tone, and begin engaging with unfamiliar language in a low-risk, fun way. This community-building activity helps normalize participation and lowers the barrier to entry before students move into more cognitively demanding reading and writing tasks. It also provides the teacher with informal data about the students’ confidence and willingness to use the language. It sets the tone and builds momentum for the rest of the lesson.

Where Flexibility Becomes Necessary

As the lesson moves into reading and writing, students’ needs begin to diverge. Some students need language support. Others benefit from modeling and feedback as they write. Some are ready to work more independently. At this point, a single whole-group pathway can limit access rather than support it.

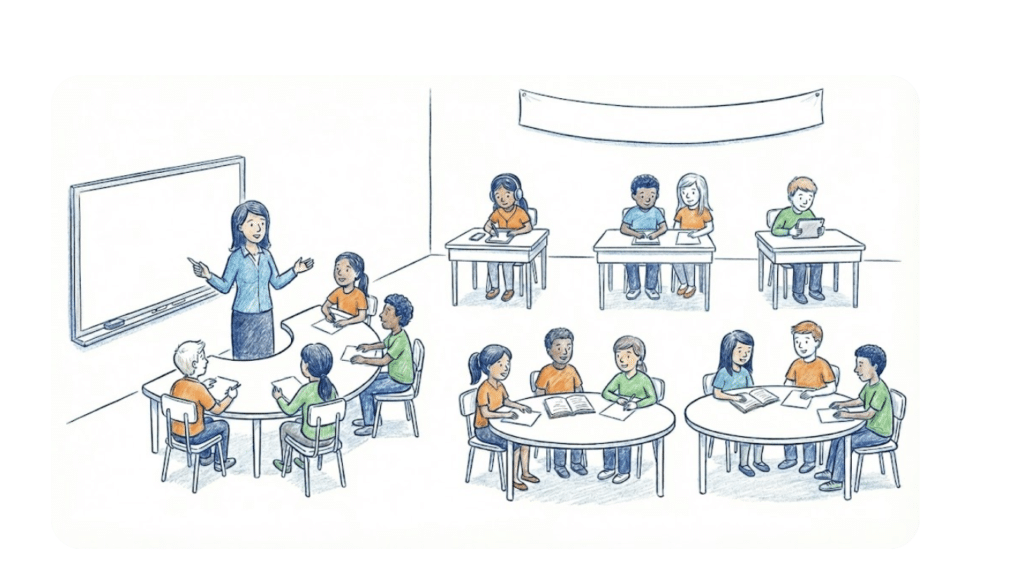

Using the cues already embedded in the lesson, I reorganized the core work into a station rotation to create space for targeted small-group instruction while giving students more control over pace and processing. No new materials were added, and the learning goals remained the same. What changed was how students accessed the work.

The Teacher-led Station

I used the teacher-led station to support the writing task, drawing on a note in the margin of the original lesson about supporting multilingual learners at different language proficiency levels. Small-group instruction made it possible to model expectations, scaffold language, and provide feedback as students were writing, rather than after the work was complete. This ensured that all students, regardless of language proficiency or writing confidence, had access to the support they needed to complete the task successfully.

Collaborative Station

In the collaborative station, students built background knowledge using the same texts and prompts from the lesson. Working in small groups allowed them to read together using the reciprocal teaching strategy to unpack the text together, ask questions, and clarify meaning. This inclusive structure shifts the cognitive work to students, supporting comprehension and discussion without requiring the teacher to lead the process. Too often in whole-group lessons, it is the teacher, not the students, doing the heavy lifting to make sense of a text.

Independent Station

An independent or partner station allowed students to engage with language playfully and repeatedly. Students could take risks, revisit tasks, and extend their thinking without pressure to perform in front of the whole class. This structure gave students greater control over the pace and processing time, while allowing them to practice and apply in ways that matched their readiness and confidence.

The Transferable Takeaways from This Example

While this example comes from a specific curriculum, the shifts it illustrates are transferable. What remained the same were the learning goals, core tasks, and materials. The lesson remained aligned with both the standards and the HQIM’s intent. What changed was the structure. Instead of assuming one pathway would work for all students, the lesson was designed to create space for targeted instruction, collaborative meaning-making, and independent practice. The teacher did not teach more content. Instead, they adjusted how students engaged with the content to meet their needs better.

This kind of flexibility strengthens Tier 1 instruction. Instead of approaching all instruction in a lockstep group, teachers can make intentional decisions to ensure lessons meet students’ needs, rather than waiting for students to struggle and require separate intervention. It also creates a more sustainable instructional experience for teachers. They can focus their time and energy on the areas where it has the greatest impact.

Wrap Up

When teachers are expected to follow lessons without deviation, their professional judgment is quietly devalued. Over time, this can erode confidence, creativity, and a sense of ownership over their work. Respecting teacher autonomy doesn’t mean abandoning the curriculum. It means trusting educators to use high-quality materials thoughtfully, adapting their instruction as needed, and exercising professional judgment in service of students. When teachers are supported to do that work, HQIM becomes a strong foundation for meaningful and sustainable teaching and learning.

Supporting Teams in Using HQIM Intentionally

If your state, district, or school is prioritizing high-quality instructional materials and grappling with how to support teachers in using them more intentionally and flexibly, this is work I regularly support. Much of my professional learning focuses on helping teacher teams and instructional coaches use HQIM to make instructional decisions that strengthen Tier 1 instruction.

I work with schools and districts to reimagine how HQIM can be used with models, like the station rotation model, to create time for differentiated small-group instruction, targeted formative feedback, and more inclusive and responsive teaching. This approach is especially valuable in systems looking to improve access for diverse learners.

If your team is interested in this type of support, please reach out. I partner with teams to offer customized workshops, coaching for teachers and instructional coaches, and longer-term implementation support.

No responses yet