I’ve experienced the phenomenon of reading a text, but when I get to the end of a page or the bottom of the article, I have no idea what the text was about. I could not answer a single question about the content of what I read. Yes, my eyes technically scanned the words, but I wasn’t thinking about what I was reading. My mind was a million miles away.

When this happens, I understand the cause. I was not actively engaging with the text. So, I take a breath, focus my mind on the text, and begin again. I know these moments do not reflect a deficiency in me as a reader. They result from a lack of focus on and engagement with the text I am reading. Unfortunately, I worry that students internalize these moments and assume they are not good readers when they don’t understand a text. Yet, reading is like any skill that we can improve with practice. We can apply strategies to help us think more deeply about what we are reading, and that help us practice active reading.

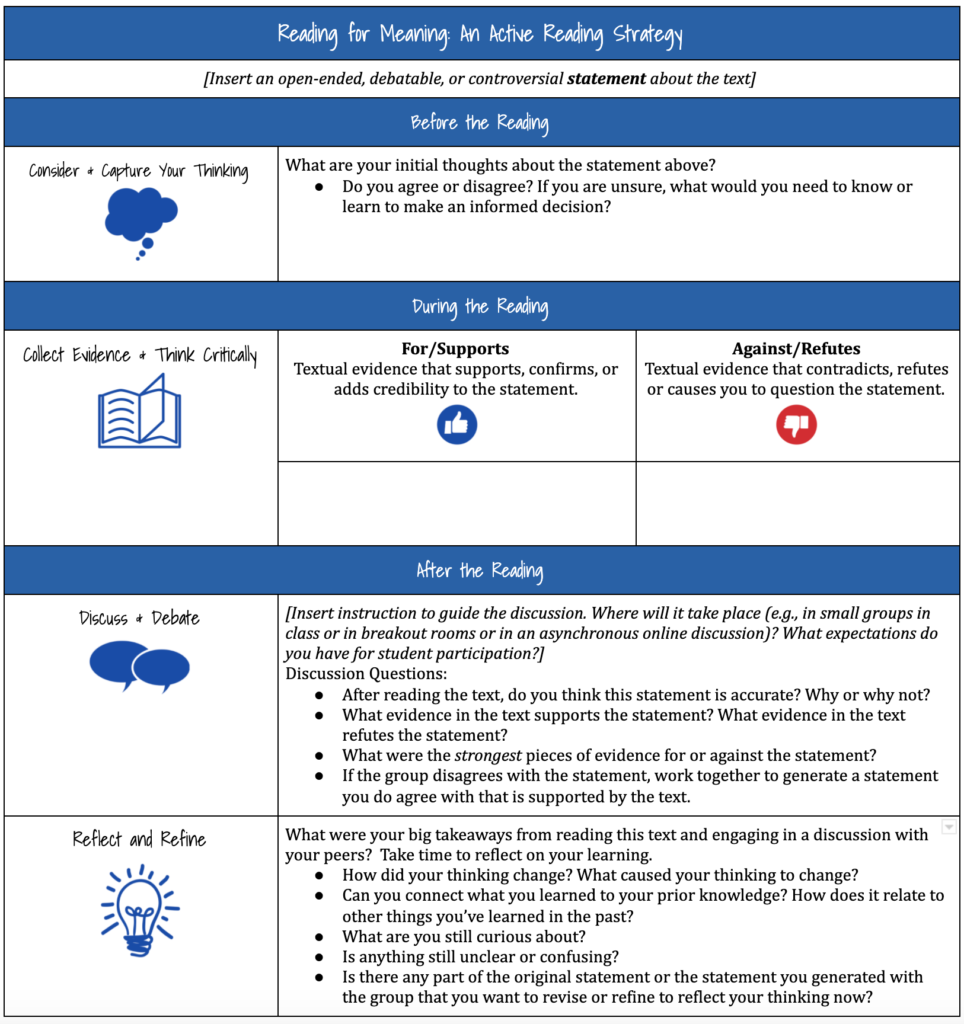

In their new book, Teaching for Deeper Learning: Tools to Engage Students in Meaning Making, my friend, Jay McTighe, and his co-author, Harvey Silver, write about an active reading strategy that encourages students to engage with texts before, during, and after reading. Their approach contrasts with classic reading comprehension questions, which students typically respond to after completing a reading assignment. Instead, this strategy presents students with an open-ended, debatable, or controversial statement to consider before they begin the reading. As they read, they analyze the text, pulling evidence that supports and refutes the statement. This prepares them to engage in a dynamic discussion with their peers about the statement and the reading.

I was immediately struck by the simplicity and power of this strategy. My mind was buzzing with how beautifully this could work in-class, online, or in a blended learning environment. I wanted to support teachers in thinking about leveraging this active reading strategy for any learning landscape, so I created the template below (with permission).

This strategy activates thinking throughout a reading task. It doesn’t matter whether a student reads a story for English, a chapter in a textbook for science or math, or an online article for history; they need to be actively thinking about what they are reading. The more effectively they engage their higher-order thinking skills, the more likely they are to make meaning as they read.

Active Reading with the Whole Group Rotation Model

Last week, I wrote about the whole group rotation, which rotates students between online and offline, individual and collaborative learning activities. This model is a great option for teachers who want to integrate technology in a meaningful way in a traditional class. It’s also a useful model for teachers navigating the challenges of the concurrent classroom in which they are teaching students in class and online simultaneously.

Let’s explore what the active reading strategy above looks like in a whole group rotation.

Before the Reading: Students read a statement and consider their initial thoughts on the statement. Do they agree, disagree, or are they unsure? What information might they need to make an informed decision about the statement? They should capture their initial thoughts in writing at the top of the document.

During the Reading: Students should have plenty of time to self-pace through the reading. Perhaps teachers grab texts or articles at different Lexile levels to differentiate or pull students who need additional support reading into a small group. That way, the teacher can guide the small group of students in reading, periodically pausing to analyze and discuss different pieces of evidence.

As students read, they should keep the initial statement in mind and collect textual evidence they believe supports and refutes the statement. This evidence should be captured in a two-column chart.

After the reading: Students engage in a conversation with their peers. This discussion can happen in small groups in a socially distant classroom or in breakout rooms. If learners are working asynchronously online, this conversation can happen in a video-based discussion using FlipGrid or in a text-based discussion inside a learning management system.

Regardless of the discussion format, students should share their thinking about the statement and offer evidence collected from the text to support their position. What evidence from the text supports the statement? What evidence contradicts or weakens the statement? Which side (for or against) has the strongest evidence? If there is disagreement among the group members, can they work collaboratively to generate a statement they all agree with?

Finally, students should reflect on what they learned. Reflection is an effective way to help students appreciate how their thinking changed as a result of actively reading and engaging in a discussion with their peers. It is also an opportunity to identify any areas of confusion or questions that still exist.

This strategy and the collection of other engagement strategies described in Jay McTighe and Harvey Silver’s book, Teaching for Deeper Learning: Tools to Engage Students in Meaning Making, can help teachers cultivate a skill set that transcends a specific teaching and learning landscape. That flexibility is what all educators need right now.

11 Responses

Tks, it seems a very good technique. 😉

Thanks, Catlin, for the great material you shared! Clear and carefully designed educational “protasis” your article is!

Thank you, Maria!

The template is great.

Just in time! Thank you!!

I love the tool kit. I will have to see how I can use it for my students. I have students who do not register on the Lexile test and others who are just below grade level (7th grade). Even though they cannot not read much they are smart.

I’m so glad you like it, Rebecca! I thought it was such a powerful strategy, and it can be used with media too if you want to mix things up. You could present a statement then ask students to listen to a kid-friendly podcast or watch a video and collect evidence as they listen and watch.

Take care.

Catlin

Love this! My kids are bored while reading texts – and I am, too, sometimes. We don’t give them a reason to push through! Caitlin, I know that you consult for StudySync. Any chance that you could model this strategy with some of their texts?

Sure! I can absolutely do that. I’ll reach out to them to see if I can write a guest blog on this topic. However, for the purpose of this conversation, let’s take the To Kill a Mockingbird excerpt. You might present students with a statement like, “The men arrived at the jail to harm Tom Robinson.” OR “The kids are scared the mob is going to hurt Atticus.” OR “The hats pulled low are a sign that the men are ashamed of their actions.” These statements lend themselves to the students analyzing the text to look for evidence for and against the statement. These are examples but you could craft any open-end, debatable, or controversial statement about the text (e.g., a character’s motivation, a central theme, the meaning of the symbol). Then as they read, they can use the annotation tool to identify (two colors) textual evidence for and against the statement. Then they can move into the discussion (in-person socially distanced or in breakout rooms).

I hope that helps!

Catlin

Thank you so much for this template and tool kit! I think that engagement can be difficult, especially with complex text. Being active before, during, and after reading can help build that critical thinking skill and comprehension. I look forward to implementing your strategy with my students.

You’re welcome, Heather!